NAFTA had been in effect for just a few months when Ruben Ruiz got a job at the Itapsa factory in Mexico City in the summer of 1994. Itapsa made auto brakes for Echlin, a U.S. manufacturer later bought out by the huge Dana Aftermarket Group. In the factory, asbestos dust from brake parts coated machines and people alike. Ruiz had hardly begun his first shift when a machine malfunctioned, cutting four fingers from the hand of the man operating it.

It seemed clear to Ruiz that things were very wrong, so he went to a meeting to talk about organizing a union. When Itapsa managers got wind of the effort, they began firing the organizers. Nevertheless, many of the workers joined STIMAHCS, an independent democratic union of metalworkers.

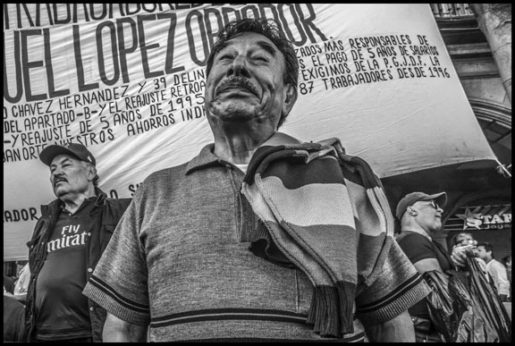

Itapsa workers filed a petition for an election but then discovered that they already had a “union” – a unit of the Confederation of Mexican Workers (CTM). They’d never seen the union contract – in essence, a “protection contract,” which insulates the company from labor unrest.

The plant’s HR manager told Ruiz that Echlin management in the U.S. said any worker organizing an independent union should be immediately fired. “He told me my name was on a list of those people,” Ruiz recounted, “and I was discharged right there.”

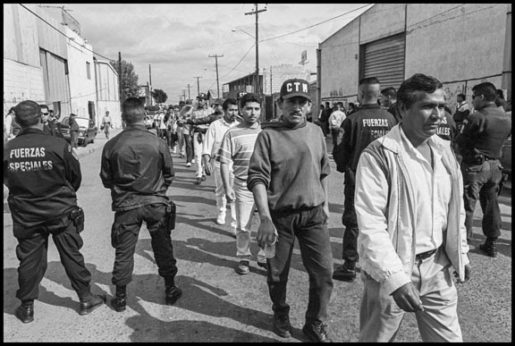

Nevertheless, there was a vote, in September 1997, to decide which union workers wanted. But before the election, a state police agent drove a car filled with rifles into the plant. Two busloads of strangers arrived, armed with clubs and copper rods.

During the voting, workers were escorted by CTM functionaries past the club and rifle-wielding strangers. Some workers were forcibly kept in a part of the factory to keep them from voting. At the polling station, employees were asked aloud which union they favored, in front of management and CTM representatives.

STIMAHCS tried to get the election canceled. But the government body administering it, the Conciliation and Arbitration Board (JCA), went ahead, even after thugs roughed up one of the independent union’s organizers. Predictably, STIMAHCS lost.

For 20 years the Itapsa election has been a symbol of all that’s gone wrong with Mexico’s labor law, which provides protection on paper for workers seeking to organize but which has been routinely undermined by a succession of governments bent on using a low-wage workforce to attract foreign investment. Dana Corporation was just one beneficiary – Itapsa has been the norm, not the exception.

In 2015 thousands of farm workers struck U.S. growers in Baja California. Instead of recognizing their new independent union, however, growers signed protection contracts with the CTM, which were certified by the local JCA. Strikers were blacklisted. Later that year workers tried to register an independent union in four Juarez factories. Some 120 workers making ink cartridges for Lexmark were fired, as were another 170 at ADC CommScope, and many more at Foxconn and Eaton.

The labor board declined to reinstate the fired workers in Juarez and Baja – following the pattern it had set at Itapsa two decades earlier. Indeed, the JNCs have been key to the defeat of workers’ attempts to form democratic unions, invariably protecting employers and corporate-friendly unions.

The new Mexican government, headed by President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO), says that’s all over. Deputy Secretary of Labor in the new administration, Alfredo Dominguez Marrufo, promises that “after all these struggles, we can finally get rid of the protection contract system. We can make our unions democratic, choose our own leaders and negotiate our own contracts. This government will defend the freedom of workers to organize. That right has existed in theory, but we’ve had a structure making it impossible. This will change.”

That could have a big impact on political life in Mexico, where corporate union leaders have had an inside track to political power and corruption. It could change the dominating role U.S. corporations have played in the Mexican economy, and affect relations between workers in both countries. Most of all, it would raise a standard of living for workers that Lopez Obrador has called “among the lowest on the planet.” In his speech to the Mexican Congress during his December 1 inauguration, the new president charged that 36 years of neoliberal economic reforms had lowered the purchasing power of Mexico’s minimum wage by 60 percent. Today, on the border, that wage comes to a little above $4 per day.

According to University of California Professor Harley Shaiken, “The Mexican government created an investment climate that depends on a vast number of low wage-earners. This climate gets all the government’s attention, while the consumer climate – the ability of people to buy what they produce – is sacrificed.”

Protecting corporations from demands for higher wages has made Mexico a profitable place to do business. Big auto companies, the world’s major garment manufacturers, the global high tech electronic assemblers – all built huge plants to take advantage of Mexico’s neoliberal economic policies, starting more than two decades before the negotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement.

That wild-west climate for investors produced more than low wages, however. Between 1988 and 1992, 163 Juarez children were born with anencephaly – without brains – an extremely rare disorder. Health critics charged that the defects were due to exposure to toxic chemicals in the factories or their toxic discharges. The Chilpancingo colonia below the mesa in Tijuana where the battery plant of Metales y Derivados was located experienced the same plague.

As the companies came south, the people came north. “During the neoliberal period [which he defines as the last 36 years or six Mexican presidencies] we became the second country in the world with the highest migration,” Lopez Obrador charged. “They live and work in the United States, 24 million Mexicans [Mexico’s population in 2017 was 129.2 million] … They are sending 30 billion dollars a year to their families … the greatest social benefit we receive from abroad.”

In his six-year campaign for office, in which he spoke in practically every sizeable town in the country, Lopez Obrador repeated what he later told the Congress – that only development “to combat poverty and marginalization as has never been done in history” would provide an alternative to migration.

“We will put aside the neoliberal hypocrisy,” he announced. “Those born poor will not be condemned to die poor … We want migration to be optional, not mandatory, [to make Mexicans] happy where they were born, where their family members, their customs and their cultures are.”

In his speech, Lopez Obrador criticized two other neoliberal articles of faith – that privatization of the state-owned section of the Mexican economy would lead to economic growth, and that pro-corporate changes in its labor law would create jobs and higher incomes.

Starting before NAFTA was passed, Mexican president Carlos Salinas de Gortari rammed through the Congress changes in the Constitution’s guarantees of land reform, to make private land ownership easier. Many of the communal ejidos, created in previous decades, were dissolved and their lands sold to investors. Farmers became wage workers on land they’d previously owned. Subsequent land reforms led to granting foreign mining companies concessions on over a third of Mexico’s territory, allowing them to develop operations even in the face of local opposition.

Prices on basic goods were decontrolled, and government subsidies on food were cut back or ended altogether. In 1998, the government dissolved CONASUPO, a system of state-run stores selling basic foodstuffs like tortillas and milk at subsidized low prices. At the same time, price supports for small corn growers were also ended. As NAFTA allowed U.S. corporations to flood the Mexican market with cheap subsidized imported corn, millions of farmers were displaced, no longer able to sell their corn at a price that paid for growing it.

“Mexico is the origin of corn, that blessed plant,” Lopez Obrador noted bitterly, “and now we are the nation that imports the most corn in the world.” He announced that a CONASUPO-like subsidized food production and distribution system would be reestablished.

Privatization marked a 180-degree change in the direction of Mexican economic policy. After its 1910-20 Revolution, nationalists believed that to be truly independent Mexico had to ensure its resources were controlled by Mexicans and used for their benefit. The route to this control was nationalization, to stop the transfer of wealth out of the country and to set up an internal market, in which what was produced in Mexico would be sold there as well.

Mexico therefore guaranteed rights to workers that U.S. unions and workers could only dream of. Severance pay was mandatory and workers had a right to profit-sharing. During legal strikes, companies had to shut their doors until the dispute was resolved. On paper, the government acknowledged the right of all people to education and housing.

In return, however, Mexican unions gave up autonomy and control of their own affairs. The government registered unions and oversaw their internal processes and choice of leaders. It never tolerated independent action by workers and unions outside its political structure. When the government changed its basic economic policy, using low wages to attract foreign investment, and producing for the US market instead of for Mexico, the government could and did punish resistance severely.

Under Presidents Salinas de Gortari and Zedillo (1988-2000) privatization reforms became a whirlwind. Among the companies and industries affected were the Aeromexico airline, the telephone company, the petrochemical industry dependent on the state-run oil company, the Sicartsa steel mill, the railroad network, many Mexican mines, and the operation of the country’s ports.

The leader of the union at Aeromexico was imprisoned after he refused to accept the company’s privatization and the layoff of thousands of workers. The head of one of the largest sections of the union for employees of the social security system, IMSS, also spent months in jail in 1995 for denouncing government plans to privatize the enormous federal pension and healthcare agency.

In 1991 the Mexican army took over the port of Veracruz, disbanded the longshore union, and installed three private contractors to load and unload ships. Hourly wages of Veracruz longshoremen fell from about $7.00 to $1.00, even as productivity rose from 18 to over 40 shipping containers handled per hour.

When the Sicartsa steel mill was privatized in 1992, wages were cut in half, and 1500 of the mill’s 5000 workers were laid off. They were then rehired as temporary labor under 28-day contracts.

The Mexican government sold the Cananea and Nacozari copper mines, among the world’s largest, to German Larrea’s Grupo Mexico at a fraction of their book value. In 1997 Larrea bought the 4052-mile Pacific North railroad, in partnership with Pennsylvania-based Union Pacific. Workers throughout northern Mexico mounted a series of rolling wildcat strikes over cuts in its workforce of 13,000 by more than half. They lost.

Thirteen Mexican financiers became billionaires during the Salinas administration, and Larrea was one of them. Grupo Mexico forced Cananea’s miners’ union to go on strike in 2009, a conflict that is still unresolved. After 65 miners were entombed by an explosion in Grupo Mexico’s Pasta de Conchos coal mine in 2006, the union’s president Napoleon Gomez Urrutia was forced into exile in Canada. He’d accused Larrea of “industrial homicide” for giving up rescue efforts after only three days.

This October Gomez Urrutia was elected Senator in Sonora on the Morena ticket (Lopez Obrador’s party-in-formation) and finally returned from Canada to take office.

The harshest privatization came in 2009 when President Felipe Calderon dissolved the state-owned Power and Light Company of central Mexico. In firing all its 44,000 workers, Calderon hoped to destroy one of Mexico’s oldest and most democratic unions, the Mexican Electrical Workers (SME). The company’s operations were folded into the Federal Electricity Commission. Private electrical generation was already permitted by Salinas and Zedillo, and Lopez Obrador’s immediate predecessor, Enrique Peña Nieto, had set up plans for private power sale to consumers.

Meanwhile, the Federal Electricity Commission itself was slated for elimination. Peña Nieto pushed a Constitutional reform through Congress to reverse the guarantee of national ownership of both the oil and electrical industries.

Far from increasing productivity and investment, however, “the damage caused to the national energy sector during neoliberalism is so serious,” Lopez Obrador charged, “that we are not only the oil country that imports the most gasoline in the world, but we are now buying crude oil to supply the only six refineries that barely survive.”

Humberto Montes de Oca, foreign secretary of the SME union, says, “The country is bankrupt. Before we can redistribute wealth we have to recover it. We know the banks will act against reversing the energy reform along with the others. We will all have to participate in order to defend any changes this new government tries to make.” The SME has established a cooperative and has regained control of seven power generation stations, along with other property that formerly belonged to the old company.

“The hallmark of neoliberalism is corruption,” Lopez Obrador charged. “Privatization has been synonymous with corruption in Mexico … The robbery of the goods of the people and the riches of the nation has been a modus operandi … In the last three decades the highest authorities have dedicated themselves to giving concessions to the territory and transferring companies and public goods, even functions of the state, to national and foreign individuals … The government will no longer facilitate looting, and will no longer be a committee in the service of a rapacious minority.”

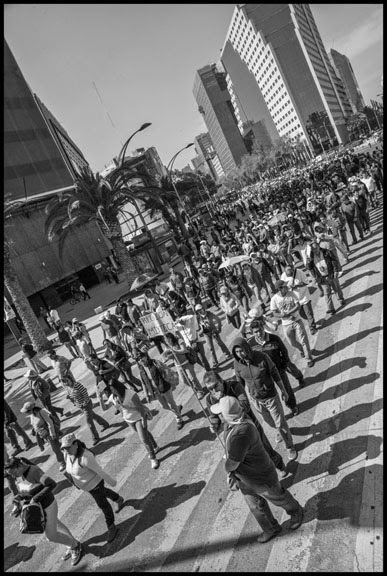

To date, only one economic reform enacted by Lopez Obrador’s predecessors has been repealed outright: the education reform that mandated standardized testing for students and testing and firing of teachers themselves. Mexico’s teachers have a long history of resistance and radical politics. More than 100 teachers in the state of Oaxaca alone were killed during their struggle over control of their union, and in defense of the indigenous communities in which they lived. Years of massive teacher strikes against the government’s education reform eventually led to a massacre in Nochixtlan in June 2016, in which nine people were gunned down by federal and state police.

The disappearance and murder of 43 students from the Ayotzinapa training school in September 2014 was also an indirect product of the corporate education reform program. Their school had a reputation for turning out radical teachers, as do many rural training schools like it, and their students came from some of the poorest families in the countryside.

Claudio X. González Guajardo, cofounder of the Televisa Foundation and the Mexicanos Primeros corporate education reform lobby, called such public schools “a swarm of politics and shouting.” He demanded the government replace them with private institutions. Following Lopez Obrador’s speech to the Congress, Gonzalez tweeted, Trump-style, “AMLO – Against the free market, against the energy reform, a retrograde, statist, interventionist, stagnant vision. The markets will react negatively. It will go very badly with us, very badly. A shame.”

In his address, Lopez Obrador had promised, “The so-called education reform will be canceled, the right to free education will be established in Article 3 of the Constitution at all levels of schooling, and the government will never again offend teachers. The disappearance of Ayotzinapa’s youth will be thoroughly investigated; the truth will be known and those responsible will be punished.” In meetings with the democratic teachers caucus, he also promised free elections in their union, the largest in Latin America. Eliminating the authoritarian group that has held power in the union for decades could shift the balance between the left and right in Mexico’s institutional politics.

Despite the move against education reform, most Mexican unions do not expect the new government to reverse the privatizations that have already taken place, at least not for the first three years of Lopez Obrador’s six-year term. Instead, they have concentrated on winning a basic reform of Mexico’s labor law, which has changed radically during the past two decades.

In May 2000, the World Bank made a series of recommendations to the Mexican administration, “An Integral Agenda of Development for the New Era.” The bank recommended rewriting Mexico’s Constitution and Federal Labor Law by eliminating its requirements that companies give workers permanent status after 90 days, limit part-time work and abide by the 40-hour week, pay severance when they lay workers off and negotiate over the closure of factories. The bank called for ending the law’s ban on strikebreaking, and its guarantees of job training, health care, and housing.

The recommendations were so extreme that even some employers condemned them. President Vicente Fox embraced the proposal, but it failed to pass the Congress. After further attempts, however, President Felipe Calderon did get a similar reform adopted in 2012. It allows companies to outsource, or subcontract, jobs, which was previously banned. It allows part-time and temporary work and pay by the hour rather than the day. Workers now can be terminated without cause for their first six months on the job.

Arturo Alcalde, one of Mexico’s most respected labor lawyer and past president of the National Association of Democratic Lawyers, called the reforms “an open invitation to employers, and a road to a paradise of firings.” As he predicted, subcontracting proliferated with disastrous results. In just one instance, Grupo Mexico replaced strikers at the Cananea mine by contracting out their jobs. Inexperienced replacements died in mine accidents, and allowed a huge spill of toxic mine tailings into the Sonora River, contaminating communities and sickening residents.

According to Benedicto Martinez, co-president of the Authentic Labor Front, the union federation to which STIMAHCS belongs, “The motivation of the government, assisted by corporate unions, was to encourage the layoff of longtime employees, who could be replaced by subcontracted workers. There are companies now where all the workers are subcontracted, who have no employees of their own at all. The conditions are very low, just slightly above the legal minimum, and sometimes below.”

Last year, under pressure from the European Union, which sought a free trade agreement with Mexico, the Peña Nieto administration had to agree to reform some of the pro-corporate labor practices. The government was forced to ratify Convention 98 of the International Labor Organization, guaranteeing freedom of association (something the United States has not done). Peña Nieto then got the Mexican Congress to pass a Constitutional reform, embodying these changes. Corporate unions like the CTM, clearly feeling threatened by the reform, introduced their own legislation in 2017 to nullify its effect. They couldn’t get it passed, however, as it became evident that Lopez Obrador would be elected the next president.

In Martinez’ eyes, the Constitutional reform is “the most advanced proposal that you could imagine. It includes union democracy, and the disappearance of the Conciliation and Arbitration Boards, which have always been complicit with the bosses and the corporate unions. In some states, a union contract is treated like a state secret, that no one is allowed to see.”

Martinez believes the reform was the fruit of many years of groups like his fighting the government. “It was like talking to a wall,” he recalls. “We were accused of being traitors to the country, because we organized international pressure with unions all over the world, denouncing the practices here in Mexico.”

Domingues Marrufo, Lopez Obrador’s Deputy Labor Secretary, agrees. “If it were not for that support from the {U.S. and Canadian] United Steelworkers and other unions, it would have been impossible to achieve the Constitutional reform.”

But changing the Constitution does not change the particular laws that govern labor activity. Implementing legislation must be passed to define rights and procedures, and set up the structure for enforcing the reform. After Lopez Obrador won the election in July, but before he took office in December, Mexican unions and labor lawyers set up a discussion group, the Citizens Labor Observatory, and debated how far the new changes should go.

Some wanted to undo Calderon’s 2012 reform completely, by reversing, for instance, the reform laws that now allow subcontracting and temporary employment. In the end, though, the consensus among the democratic unions was to limit the proposal to the implementing legislation that gives workers the right to vote for the union and union leaders of their choice and to approve their contracts. It was clear this was Lopez Obrador’s favored choice. As Mexico City Mayor in 2000, he had appointed another dean of Mexican labor lawyers, Jesus Campos Linas, as head of the city’s labor board. Campos Linas then made public an estimated 70-80,000 protection contracts whose contents had never been released to the workers they covered.

Two days before Christmas, deputies from Lopez Obrador’s Morena Party-in-formation introduced their labor reform bill into the Chamber of Deputies. It will abolish the JCAs and substitute an independent system of labor tribunals. Unions will be independent of the government and business, and leaders must be elected by a majority of the workers. Union contracts will be public and must be ratified by the majority of the workers in a free and secret vote.

Sweeping though it will be, the new labor law is just a beginning. On taking office, Lopez Obrador appointed Maria Luisa Alcalde the new Labor Secretary. She is a former legislator, daughter of labor lawyer Arturo Alcalde, and at 31 the youngest person in AMLO’s cabinet. “She is very clear that the democratization of the unions will create a new situation and our society will have a much better chance to raise living standards,” Dominguez says. But, he warned, “We aren’t accustomed to organizing ourselves. We’re used to waiting for some powerful person to come from above to help us.”

And while waiting for unions and workers to use the new law, the government is still faced with many legacy strikes and fights inherited from 36 years of neoliberal administrations. The telecommunications reform, for instance, mandated the breakup of TelMex, the old telephone monopoly sold to billionaire Carlos Slim. In February it is set to be divided in two, a move the telephone workers union bitterly opposes. They are threatening to strike if it isn’t stopped.

In the mid-1990s the telefonistas, together with the Authentic Labor Front (FAT) and two other unions, formed the National Union of Workers, an independent labor federation. They supported Lopez Obrador very strongly. “Our corporate elite had to respond to the fact that the vast majority of Mexicans voted for him, and were unable to use their electoral fraud strategy to deny him victory, as they had in the past,” says Victor Enrique Fabela, vice-president of the union.

But he doesn’t believe that Lopez Obrador will simply do what unions ask, pointing out that the new president invited Carlos Slim to hear his inaugural speech to the Congress, an invitation not extended to the union’s general secretary, Francisco Hernandez Juarez. Further, long term operating concessions have been renewed for Televisa and TeleAzteca, two media giants with a record of rightwing politics. “We have to be critical,” he cautioned, “while understanding that we have to support the direction AMLO is moving.”

The strike in Cananea has yet to be settled, and there and in Nacozari, two of the world’s largest copper mines, the miners’ union was forced out by previous JCA decisions favoring the CTM and Grupo Mexico. The communities on the Rio Sonora are still suffering the health effects of the toxic spill, three years later. And on November 29 at the giant PKC wire harness plant in Ciudad Acuña, just two days before Lopez Obrador was sworn in, CTM thugs marched into the facility, shouting “Mineros Afuera!” [Miners’ Union Out!] as workers were about to vote on the miners’ union as their representative. They overturned ballot boxes, the election was canceled, and the mineros say its representatives were beaten.

“We all want a change,” charged Moises Acuña, the mineros’ political secretary. “We have a chance to move forward now, and we have to use it.” Meanwhile, a new federation of independent unions in the auto industry has also been formed and plans to fight with the CTM over the right to negotiate contracts with the industry’s giants.

In dealing with the workers’ upsurge and the emergence of new unions, however, Lopez Obrador’s government faces a complex situation. The JCAs will disappear and the new tribunals will be formed. But there are no judges yet, and they won’t be in place for the first three years. The tribunals have to be funded, and judges and personnel trained in administering a completely new law.

“But during that time, in order to represent workers and negotiate, a union still has to be certified by the authorities,” Martinez says. “There must be some way to ensure that the workers have approved this union, and this approval must take place before any negotiation begins. Plus, who are the inspectors now responsible for investigating the outsourcing, to make sure it’s legal? We need an army of them, and there’s no money to hire them.”

Despite the institutional challenges, Dominguez believes that the time has arrived when Mexican workers may be able to reshape their nation. “Today many workers live in poverty, on one or two dollars a day. This is the fundamental problem. But we’re not just fighting for an economic goal, not just for decent wages, but for the revitalization of the democratic life of workers, of our unions and the organizations we belong to.”