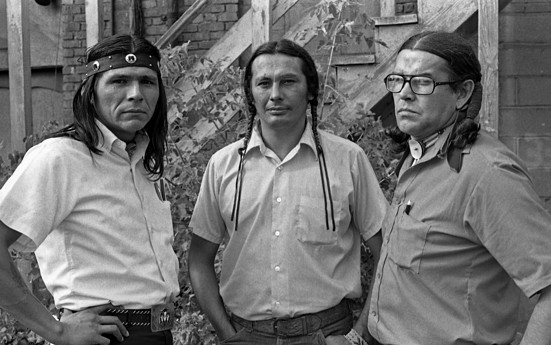

Nothing changed the face of Indigenous people and their culture like the American Indian Movement, founded in 50 years ago on July 11, 1968 in Minneapolis, Minn. Three Ojibwa Indians and graduates of “Indian finishing school”—the Minnesota State Penitentiary—were Clyde Bellecourt, Dennis Banks, and George Mitchell were the first leading figures. Other important early members included Eddie Benton Banai, Vernon Bellecourt, and later Russell Means. John Trudell served as national media spokesperson.

The beginnings of AIM in Minnesota were rooted in efforts to combat police brutality in Minneapolis, but it quickly expanded and committed itself to uniting all Indigenous persons to uplift their communities and promote cultural pride and sovereignty.

Between November 20, 1969, and June 11, 1971, the Occupation of Alcatraz took place. On that island prison, 89 American Indians and supporters, led by Richard Oakes, LaNada Means, and others seized control. They chose the name Indians of All Tribes (IOAT), and John Trudell was the spokesperson. According to IOAT, under the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868) between the U.S. and the Lakota, all retired, abandoned, or out-of-use federal land was returned to the Native people who once occupied it. Since Alcatraz penitentiary had been closed on March 21, 1963, and the island had been declared surplus federal property in 1964, a number of Red Power activists felt the island qualified for a reclamation.

The Occupation had a brief but somewhat direct effect on federal Indian Termination policies and established a precedent for Indian activism. Oakes was shot to death in 1972, and AIM was targeted by the federal government and the FBI in COINTELPRO operations.

AIM’s national exposure grew in 1972 during their Trail of Broken Treaties. Members started in San Francisco and ended up in Washington, D.C. just on November 3rd, just as Richard Nixon was about to be re-elected. The four-mile-long procession arrived early on the morning of and presented the Nixon administration with a 20-point proposal for improving U.S.-Indian relations.

The first of the Indians’ 20 Points demanded the restoration of their constitutional treaty-making powers, removed by a provision in the 1871 Indian Appropriations Act. The next seven concerned recognition of the sovereignty of Indian nations and the revalidation of treaties, including the Fort Laramie Treaty. The fundamental demand at the core of all these was that Indians be dealt with according to “our treaties.”

Other points addressed such matters as land reform law and the restoration of a land base which would permit those Indians who wished to do so to return to a traditional way of life. From the U.S. government’s point of view, recognizing or negotiating treaty claims all over the country might necessitate the return of vast tracts of America to the true owners, a very dangerous idea indeed!

When the government refused dialogue with the Indians, the protestors occupied the Bureau of Indian Affairs building. The government negotiated with the Indians then, but only to end the occupation, not to resolve their original 20-point list of grievances. The government promised to look into the grievances (it never did) and not to prosecute the Indians for the BIA takeover (a promise broken like all the others).

To defuse the situation and end their own embarrassment, the government eventually provided vehicles and an early-morning police escort out of town plus under-the-table money ($66,000) to pay the Indians’ return travel expenses. (Year later, in a documentary, John Trudell says that Nixon’s administration came up with the money because none of the Indigenous warriors had gas money. The $66,000 was used to get them out of Washington.)

After the Trail of Broken Treaties, AIM was classified as “an extremist organization” by the FBI, and on January 8, 1973, the leaders on the Trail were added to the FBI’s list of “key extremists.” From that point, an organized “neutralizing” of AIM leaders was begun. (This is highlighted in the COINTELPRO booklet on Leonard Peltier’s website.)

Following the BIA takeover, AIM chapters nationwide were the focus of an intensive investigation, and individual members were targeted for arrest and prosecution. A few weeks after his return from Washington, D.C., in November 1972, for example, Peltier was accused of the attempted murder of a Milwaukee police officer. His claim that he had been set up by the police was eventually supported by several witnesses, including the police officer’s girlfriend, who said the officer had waved around one of Peltier’s pictures, sent to the local police from FBI headquarters, announcing his intention of “catching a big one for the FBI.”

In relation to Wounded Knee II, the FBI caused 542 separate charges to be filed against those it identified as “key AIM leaders.” This resulted in only 15 convictions, all on such small offenses as interfering with a federal officer in the performance of his duty.

Having identified AIM as an extremist threat to the United States, the Department of Justice conducted such prosecutions over a two-year period, jailing AIM members and ensnaring them in lengthy court proceedings, thereby preventing further political activity. As noted, this strategy met with only limited success, and the FBI’s war against the American Indian Movement escalated.

A six-page FBI memo, dated April 24, 1975, “The Use of Special Agents of the FBI in a Paramilitary Law Enforcement Operation in the Indian Country,” shows that two months prior to the Oglala shoot-out, the FBI was preparing for a major armed confrontation with AIM.

In May of 1975, the FBI began a sizable buildup of its agents, mostly elite Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) members, on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. In June 1975, SWAT teams from numerous divisions were designated for special assignment at Pine Ridge.

A June 1975 FBI memo, discovered much later, referred to the potential need for “military assault forces” to deal with AIM members. (It should be noted that the use of military force by the U.S. government at Wounded Knee in 1973 was ruled unlawful by the courts.)

At the same time, the FBI “aided and abetted” Tribal Chairman Dick Wilson, who was intent on stamping out any opposition to his administration by any means. The Bureau, it has since been discovered, provided weapons to Wilson’s vigilantes—the Guardians of the Oglala Nation (GOONs)—and stood by as the politically motivated injury and murder rates on the reservation climbed.

As there was no corresponding AIM buildup on the reservation, nor preparation on the part of AIM members for a confrontation with the authorities (despite the FBI’s later false claim of the presence of bunkers at the Jumping Bull compound), there is little doubt that the FBI alone set the stage for the tragic shoot-out at Oglala on June 26.

The American Indian Movement survived the turmoil of the 1970s. The FBI failed in its mission to destroy AIM largely because it is not an organization as such, but what its name states outright—a movement, a continuous series of actions moving towards an objective. Regardless of mistakes made during that time or the personalities involved, there is no doubt that the men and women of AIM raised the consciousness of Indigenous peoples, sparked cultural pride, and engendered the Native activism seen today.

Special note should be made that most AIM chapters are sanctioned by the Minnesota headquarters. Oklahoma has always had an autonomous contingency comprised of the late Carter Camp and Michael Haney. Living members include persons such as Richard Ray Whitman, Ben Carnes, Lavetta Yeahquo, David Hill and Carter’s sister, Casey Camp Horinek. Their spiritual advisor was Phillip Deere from Okemah, Oklahoma.

David Hill’s writing on AIM as a verb and not a noun defines where AIM is today. There still are sanctioned groups by the original Minnesota AIM, but there are resistance warriors popping up with water camps in support of Indigenous Sovereignty, just as AIM has always advocated. So there is still the warrior spirit within the younger generation fighting for treaty rights still as a verb, AIM, not a noun.

The resistance shown during and after Standing Rock is due to the original AIM movement in the early 1970s. Indigenous warriors today represent those that fight for the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, the water camps, the pipeline protests, and even for their basic right to attend college, and of course Leonard Peltier’s freedom. Indigenous warriors shall always protect the culture and customs of their Indigenous ways.

AIM forever! Forever AIM!

Sources: Two great video histories are available on YouTube: Video 1 and Video 2.