This will be a review/appreciation of a fresh new crime novel by one of our regular contributors to People’s World, the Paris-based American scholar Dennis Broe. Before we get down to the nitty-gritty, I thought you might like a short introduction to the author.

Dennis Broe is a scholar and professor, who has taught at The Sorbonne, Rutgers, and Hofstra, with a specialization in 1940s Hollywood cinema, the crime film or film noir, and art and culture of the Cold War.

He is a film and television critic on Arts Express on the Pacifica Radio Network, the host of the television series TV on TV on Art District TV in Paris, and a film, television, art and literary critic for the British daily Morning Star as well as Culture Matters, Crime Fiction Lover and, as noted above, People’s World.

Broe’s book titles reveal a mind boiling over with prolific creativity and insight, and hint at his sociopolitical orientation. They include Film Noir, American Workers and Postwar Hollywood (University Press of Florida, 2010); Class, Crime and International Film Noir: Globalizing America’s Dark Art (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014); Cold War Expressionism: Perverting the Politics of Perception/Bombast, Blacklists and Blockades in the Postwar Art World (Pathmark Press, 2015); Maverick or How the West Was Lost (Wayne State University Press, 2015); and Birth of the Binge: Serial TV and the End of Leisure (Wayne State University Press, 2019).

Knowing everything he knows about the noir period of American film, he has finally (inevitably?) set his hand to writing his own potboiler, Left of Eden—a titular nod to East of Eden, the 1952 novel by John Steinbeck, and to the 1955 film of the same name, starring James Dean, Julie Harris, Raymond Massey, and Burl Ives, ironically directed by HUAC informant Elia Kazan.

Broe calls Left of Eden “A Harry Palmer Mystery,” after the LAPD-turned-private investigator who is the protagonist of the tale, implying that he has further adventures of the smart, risk-taking P.I. up his sleeve. I hope so! Those who like their scotch spiked with a bracing shot of Marxism will feel well rewarded.

Left of Eden is unquestionably a classically structured genre P.I. novel, tersely written—the standard adjective “hard-boiled” most certainly applies. A reader sits back to enjoy 259 pages deploying the writer’s skill at taking us on a wild rollercoaster ride through the many physical and social environments Los Angeles of the late 1940s had to offer. We dash from palatial mansions to studio lots with the glamorous stars to seedy offices and dives, to tiny bungalow apartments where wannabe starlets pool resources to live until their big break comes along. For most, of course, it never will in this predatory company town.

Many quickly fall down on their luck: “I thought once again,” the socially conscious narrator relates, “about the dangers for young women in a town that had few boundaries at nighttime and an overdose of morality in the daylight.”

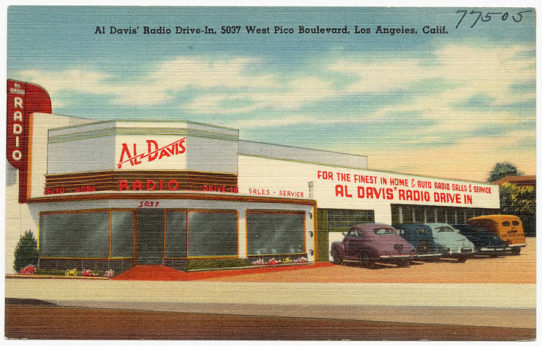

We also take some hair-raising car rides and chases through L.A.’s winding canyons, suburbs and deserts on the rim of the city, and to the downtown of institutional headquarters. Even a side trip to the potato farms of Idaho! Just like in films and TV of the period, no one is ever stuck in freeway gridlock or has trouble finding a parking place! And no one, even in that gas-guzzling era, pauses to pull into a service station to fill up.

If the intense condensation of events—murders, blackmail, beatings, break-ins, fires, mobsters, intrigues, plots, threats, slander, hidden rooms, photo exposés, safecracking, explosions, psychoanalysis, sex and much, much more—challenges the credulity of the reader with its preposterous exuberance, well, we already know the genre demands an extraordinary commitment to suspension of disbelief if we are to reap the pleasure of breathless, edge-of-your-seat thrills.

Broe’s plot-driven style may be exactly according to type, though he has his own flourishes. “He definitely smelled cop on me,” Harry Palmer says of a tough Hollywood union organizer, “and gave me a look that indicated that I was persona very non grata.”

But what sets Left of Eden apart is its setting at the beginning of the Blacklist era. The very first chapter opens with the infamous Waldorf Hotel statement, whereby the studio chiefs announced they were preparing to rid the Hollywood ranks of communists both real and imaginary.

Characters in and out of fiction

Although his characters are fictional, he models them closely on familiar names and faces from the era. The male lead, under investigation for his leftist sympathies, is Jason (Gabby) Gabriel, who had recently starred in an independent studio’s boxing movie, very much like the ill-fated John Garfield in the 1947 Body and Soul. If Broe assigns these actors fictional names, it’s also important to remember that most of the actors themselves had fictional names.

Other important characters include Eva Knox (Ava Gardner)—her name drawing attention to two of her most alluring features—and Lina Trainor (Lana Turner), with the same probably apocryphal backstory of having been “discovered” in a Schwab’s drug store. Top of the Line studio head Harvey Bauer is a clear takeoff on Louis B. Mayer of MGM, whose logo is not a lion but a cheetah.

Among the union leaders, writers and directors, we meet Henry Slawson, a thinly disguised pen portrait of West Coast Communist cultural commissar John Howard Lawson. Mick Polski sounds an awful lot like radical writer-director Abe Polonsky. Many other characters, such as producer Daniel Sezlik (David O. Selznick) or gangster Bunny Seager (Bugsy Siegel), suggest real-life prototypes, and other Hollywood names and allusions are sprinkled throughout. In addition, on top of a number of scurrilous, criminal FBI agents in the plot, we actually have J. Edgar Hoover himself turning up in Broe’s pages, as well as FBI’s reliable collaborator Walt Disney.

Palmer meets Bauer in his MGM office and notices portraits of Bauer and Hoover in a diptych on his desk. “Are you two in love?” Palmer asks.

“That elicited a cock-eyed smile and an honest response. ‘I keep Mr. Hoover’s photo on my desk for everyone to see, and he keeps my file buried in his archive. It’s a fair trade.’”

The blacklisting industry is well rendered, the innuendo, the threat, the bad publicity, the celebrity listings in Red Channels, and Benny Bilkerson’s rumor-mongering, anti-Communist rag Deadline Hollywood.

Having said which, I would not call this a roman à clef, however much fun it may be to identify the characters with their historical models. I do not believe the author means to draw any particular conclusions about those actual people from the facsimiles he creates in his whodunit.

Political clarity

With all the noir fiction and film set in Los Angeles of that period, it does not seem as though any of those works until now has used the Blacklist as a backdrop. Broe’s crystalline commentary on Hollywood history and practice distinguishes his writing from the run of the genre. While we are used to writers who are cynical and bitter, angry, frustrated and escapist, we do not often get the political clarity that we find here.

Early on, as if laying the groundwork for the larger story Broe wants to tell, he has Slawson saying:

“Look this is much wider than Hollywood. It’s a general attack on unions and progressive forces in this country, with Hollywood as the symbol. We organized successfully into a collective bargaining guild after a very hard eight years, now we’ve had a regular contract for six years. When the craftsworkers, our brother and sister painters, set builders, and technicians formed an anti-sweetheart union, we backed them, and they struck the studios. We got their attention.”

One of Hollywood’s fears was that leftist writers might—and occasionally did—insert some line skeptical of the genius of capitalism and the market system. As if to underscore their point, with the freedom he has as a novelist, Broe has Harry Palmer recalling, as no character in a Hollywood movie of the era would have been permitted:

“I left reflecting on the nature of not just the movie business, but business in general, where the line between resounding success and utter failure was often thin. These people were masters of living on the edge, never knowing what the next day would bring. And they did not mind having those working for them living the same way. Their life was a floating crap game. They didn’t see why their own employees, the painters like those that Ferrell championed and the screenwriters that Slawson organized, shouldn’t also live life on the brink—only out on their ledge they would not have their own wealth, rich friends, or the government to cushion their fall.”

Harry Palmer renders a tender, resigned eulogy to one of the victims of the system who winds up dead: “He was a good man and had tried to make a difference in a world that was growing ever more vicious by the minute. He had gotten caught in the middle of forces that were much bigger than him and his little studio Democritus, and they had claimed him.”

Reflecting the author’s own research interests, he mentions the work of Edward Bernays, an anti-communist propagandist and philosopher of the psychology of public relations and modern advertising (and incidentally, a nephew of Sigmund Freud).

Broe is also interested in the issue of illusion vs. reality, focusing on the part the actors’ “doubles” play: These are not just stunt players who have similar builds and can be dressed and made up to impersonate the bankable property, and who can be spotted in nightclubs with other (real) bankable stars, to be photographed for the Hollywood gossip sheets, while the real actor is actually on a bender, or shtupping the pool man or whatever. The “double” role, in fact, is integral to the novel’s plot.

Behind the Blacklist

Broe points to a number of factors that underpinned the Blacklist and why it emerged at that particular moment within the larger anti-Communist and anti-union narrative. One was the emergence of television, which threatened to keep people at home watching entertainment content for free. Another was suburbanization, which removed people from the downtown movie houses. Also, the film industry had lost markets in Eastern Europe—and shortly would lose more in China—owing to the rise of alternative, non-Western social systems there: Anti-Communism was in part a rollback attempt to regain those consumers.

In addition, the studio system was drawing to an end, an exploitative set-up whereby actors were virtual peons unable to escape long, seven-year contracts. In one interview Palmer has with Bauer, the studio head admits the Blacklist will save them money, decreasing salaries and sowing suspicion, competitiveness, and servility. And finally, the studios themselves were under attack for their vertical monopolistic control of theaters which created a hierarchy of favored film outlets versus lowly neighborhood houses forced to show the studios’ B films.

Broe also touches on the homophobia of the era, linking the political establishment’s persecution of both the lavender and red persuasions.

In the presumptive Harry Palmer series to come, we will undoubtedly get to know our hero better. As a reader, I felt his heightened urbanity a stretch, at least without some ’splaining, as familiar characters of the era might say. Within the space of a few pages early on, Palmer refers to Rodin’s Gates of Hell, the Borgias, and Hadrian’s Wall, and later on to Millet’s painting The Angelus, not the kind of erudition one might ordinarily expect from a Los Angeles policeman. Had he attended some upper-crust boarding school? Did he minor in art history at college?

In the presumptive Harry Palmer series to come, we will undoubtedly get to know our hero better. As a reader, I felt his heightened urbanity a stretch, at least without some ’splaining, as familiar characters of the era might say. Within the space of a few pages early on, Palmer refers to Rodin’s Gates of Hell, the Borgias, and Hadrian’s Wall, and later on to Millet’s painting The Angelus, not the kind of erudition one might ordinarily expect from a Los Angeles policeman. Had he attended some upper-crust boarding school? Did he minor in art history at college?

In one other aspect, Broe might have been somewhat more true to the Los Angeles of that time: racial diversity. There are Negro (the term used at the time) servants and household help around, but no people of color with even auxiliary roles to play in the story. Although there is sufficient attention played to the Jewish backgrounds of some of the blacklisters and blacklisted both, at a time when there was still widespread anti-Semitism. He might have created space for one or more Japanese-, Chinese-, Filipino-, Mexican- or African-American characters to fill out the cast.

Diligent scholar that he is, Broe appends a bibliographical note to guide readers toward three other sources that helped him to fill out the history of the era: Hard-Boiled Hollywood by Jon Lewis, and Class Struggle in Hollywood and The Final Victim of the Blacklist: John Howard Lawson by Gerald Horne.

Left of Eden

By Dennis Broe

Pathmark Press, 2020