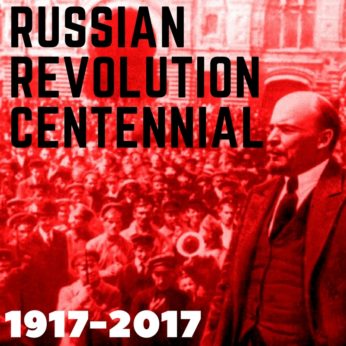

The Centennial of the Russian Revolution

November 7, 2017 marks the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution and the establishment of the world’s first socialist state. To commemorate the occasion, People’s World presents a series of articles providing wide-angled assessments of the revolution’s legacy, the Soviet Union and world communist movement which were born out of it, and the revolution’s relevance to radical politics today. Other articles in the series can be read here.

The October Revolution took place 100 years ago, on November 7, 1917. Even though the Soviet Union no longer exists, the revolution which gave birth to it reverberates still as one of the greatest history-changing events of the 20th century.

Millions of Russian workers and peasants engaged in an act of self-emancipation. Everything that followed provides those seeking a modern 21st century socialism a wealth of lessons, from both its achievements and mistakes.

Millions of Russian workers and peasants engaged in an act of self-emancipation. Everything that followed provides those seeking a modern 21st century socialism a wealth of lessons, from both its achievements and mistakes.

The October Revolution occurred in a stormy and desperate time of barbaric world war, poverty, hunger, and insurrection. The demands propelling it were simple: peace, land, and bread.

It marked the beginning of the world’s first great socialist experiment, the first break with the system of global capitalism. Millions of ordinary working men and women were charting the unknown. They carried no blueprints and tried building socialism in conditions not of their choosing. From its inception, the Soviet Union’s path was shaped by the harshest of circumstances: the legacy of feudalism, theocracy, and a violent and repressive autocratic state.

It inherited a Russia that was the “prison house of nations,” a brutal oppressor and exploiter of other nationalities and peoples. It was a land characterized by oppression of women, anti-Semitic pogroms, and repression of Islam. The industrial working class was tiny and the level of industrial development low. Illiteracy was the norm for millions, and there was little civil society, and only hollow supposedly democratic institutions.

Without pause, the Soviet Union was forced to rebuild from the devastation of World War I while defending itself against hostile encirclement and invasion by capitalist powers, including the United States. Many U.S. working people showed their solidarity for the Soviet Union and protested the U.S. intervention, even though they lacked the political power to prevent the attacks.

The inspirations and the setbacks of the early decades

Against incredible odds, the revolution inspired hope and unleashed creative energy. Millions of workers and peasants threw themselves into building a new society. Under the leadership of Lenin and the Bolsheviks, the Soviet Union adopted the most advanced democratic constitution the world had yet seen. It represented a government led by workers and peasants, established new democratic forms, equality for women and formerly oppressed nationalities, and basic rights to healthcare, education, and housing were enshrined. It declared the people the stewards of the nation’s vast natural resources.

Once the revolution was defended and after initial policy mistakes, the Soviet Union embarked on construction of a mixed economy guided by the New Economic Policy (NEP). The NEP was a policy that fit the actual state of development facing Russia, not an imagined or abstract one. It legalized multiple forms of property ownership, including private property, particularly of small landholdings, and foreign investment. The policy acknowledged that building socialism would be a protracted process; even after a socialist revolution, class society with all its restraints and inequities would be a feature of socialist construction for years to come.

Had Lenin lived, perhaps history would have turned out differently. But he died prematurely in 1924 and once Stalin assumed leadership, the NEP was scrapped in favor of forced expropriation of agricultural lands, collectivization, the centralization of power, and near total state ownership of industry.

With the threat of fascism rising in Germany, and its military machine aimed squarely at obliterating the world’s first socialist oriented state, the Soviet Union was forced into accelerated development. Under Stalin, this forced march was combined with fear of enemies, foreign and internal, real and increasingly invented. Political differences were viewed as political threats, and a culture of uniformity prevailed. Authoritarianism led to the enshrinement in the constitution of the Communist Party as the sole governing body and the development of a cult of personality around Stalin.

The campaign of fear reached its peak with the years of terror in 1937-38, when untold numbers of socialist patriots were executed and imprisoned, including substantial parts of the military general staff and Communist Party leadership.

Despite the terror of the ’30s, the now industrialized Soviet Union played the decisive role in the defeat of fascism in World War II. But the Soviet people bore an incalculable burden: Twenty-two million died and most of the country’s industrial and agricultural infrastructure, cities, villages, and farms lay in ruins.

Before it could rebuild itself from the rubble of World War II, the Soviet Union was forced to divert vast resources to the Cold War nuclear arms race with the United States and heightened competition with global capitalism.

The barrage of assaults of the first few decades of the new nation’s existence comprised an almost impossible set of circumstances for the world’s first socialist experiment. Every aspect of its development and its political and cultural life were impacted. The desperate and underdeveloped conditions and resulting chaos were fertile ground for the rise of Stalin and all subsequent crimes, imprisonments, and executions.

Moving on from Stalin

The Soviet Union may have survived Stalin, but it paid a price. The image of socialism and communism and the claim to democratic and moral authority suffered immeasurably. Marxism, as a creative body of thought, became stultified and dogmatic. This legacy, which seemed to contradict socialism’s democratic and humanitarian ideals, and the inability to fully overcome it, were also important factors in why socialism ultimately collapsed in the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc.

Despite all these negatives, the Soviet people could boast of vast achievements: modern industrial production that rivaled the U.S.; the ability to feed, clothe, and house its people; high-level scientific and technological development; universal literacy and access to health care and education; developed arts, sports, and culture; and formal social and economic equality for women and formerly oppressed minorities.

It provided immense aid to national liberation and anti-colonial movements, including Vietnam, Cuba, and the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. It assisted developing nations, funded modern infrastructure projects, and educated countless scientists, engineers, and other personnel around the world.

The Soviet Union and socialist-oriented states acted as a global counterweight to U.S. imperialism. It was the Soviet Union that took the first steps to end the Cold War arms race by unilaterally announcing a moratorium on nuclear testing and deep reductions in military personnel and weapons in the 1980s.

Competing with an economic system where exploitation was outlawed, and people came before corporate profits, capitalist countries around the world, including the U.S. capitalist class, were forced to make concessions to workers’ demands. Similarly, to avoid the appearance of hypocrisy, concessions were made on issues of racial equality.

Even with all the gains, there were, not surprisingly, many mistakes made in this period, too. They included wrong assessments of the level of socialist development that had been attained, premature egalitarianism, wage leveling, the declaration that national equality had been achieved, the persistence of Great Russian chauvinism, the inability to transition to economic and political decentralization, and the despoiling of the environment.

The Soviet Union never sufficiently developed genuine grassroots forms of democracy and instead relied on administrative methods. Pluralism of political parties and movements was never permitted. Religious faith was stigmatized and church properties confiscated. Suppression of dissent substituted for the messy battle of ideas and the give-and-take of democratic civil society. The importance of the latter is particularly obvious in our day, given rise of the internet and social media. The information revolution demands engagement rather than directives, something the Soviet system would have trouble dealing with.

The Soviet Union was unable to decisively break with this economic and political model, which, when combined with negative external factors facing the country, brought on a period of crisis in the 1970s and ’80s. In response, the Communist Party leadership eventually launched a program of reforms on the prompting of Mikhail Gorbachev. These reforms were, at least at first, aimed at deepening socialist democracy, including at the workplace, permitting an independent media, demilitarization, and restructuring the economy.

Against the background of these needed reforms, however, Soviet leaders were deeply divided, weakened, and paralyzed—including within the Communist Party. By this point, the bureaucracy had become too entrenched, careerism too rampant, the centralized model too embedded, resistance to change too deep, and resentment toward the CPSU too widespread.

Demilitarization of the economy stalled, and other reforms, including a looser federation of Soviet republics, spun out of control. Gorbachev’s downgrading class struggle and the haphazard way that reforms—including workers’ self-management, state enterprise autonomy, and the institution of market mechanisms—were introduced was disarming and confusing. Out of the chaos, pro-capitalist and nationalist forces and corrupt elements like Boris Yeltsin eventually gained the upper hand.

In 1991, after 74 years, the Soviet Union collapsed. Its death represented an immense tragedy and loss to humanity, gave a boost to global reaction, war, anti-socialism, and U.S. imperialist aggression.

Above all, it represented a colossal loss to the Soviet people. Out of its collapse rose a class of oligarchs who enriched themselves by stealing the vast wealth created by the Soviet people and by restoring exploitation. Today, the Russian people live in impoverishment and under repressive authoritarian rule.

Learning from the Soviet experience

What lessons can be learned?

People, including revolutionaries, make mistakes. But they can be corrected, including by carrying out needed reforms, if revolutionary movements, including their leaderships, promote the capacity for sober self-reflection and flexibility and avoid dogma.

People build socialism under conditions not of their choosing. Socialist revolutions take place under very different conditions shaped by a nation’s history, level of class and socialist consciousness and unity, material development, and store of resources. There are no eternal models for either the path to achieving working class political power or for the development of socialism.

U.S. socialism will be based on our political and historical realities, the high level of cultural and material development achieved in our country, and our long history of struggle for expanding democratic rights. It will be able to take into account the hard-won lessons of the world’s working class and people.

It will be shaped by the conscious activity of the multi-racial American people to expand economic and political democracy; overcome social, racial, and gender inequity; achieve a better, more secure, humane life and creative work; pursue a sustainable path of development; and demilitarize the economy and society.

Socialism in the United States can be achieved peacefully and democratically through the electoral arena. Its achievement will be a protracted process encompassing many stages. It will not occur through the barrel of a gun. In fact, Frederick Engels suggested as much in the late 1880s with the winning of the universal franchise. “The day of the storming of the barricades is over,” he said.

A mass movement of the overwhelming majority of the American people who are conscious of the need for socialism and working class political power can and must compel the capitalist class to accept a path chosen by the majority and restrict its ability to resist or use violence.

Central to all of this, of course, is the struggle for democracy, the extension of political and economic rights, and the growing engagement and conscious participation of a majority of working people in political activity and civil society.

One hundreds years later, the flame lit by the October Revolution burns bright. It is our task to honestly analyze it and learn the lessons of both its achievements and its shortcomings for the socialism of the future.