This is part 2 of a series. Read part 1 here.

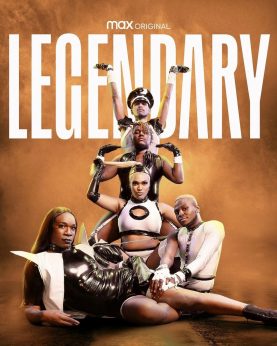

The authentic New York City ballroom scene, though more than half a century old, remains largely underground. Other than Madonna’s 1990 hit single, Vogue, the 1991 documentary Paris is Burning, and new TV series and competition shows such as Pose and Legendary, the art of voguing and “walking a ball” remains unseen by most Americans.

How often do heterosexual white workers sit down and think to themselves, “What would it be like to be gay, lesbian, or transgender in this world?” or “What would it be like to be both Black or brown AND gay in this world?” The truth is we are all oppressed under capitalism. But these special questions regarding race and gender in the struggle to defend and expand democracy in the post-Trump era cannot be ignored.

The ballroom scene, however, is the perfect place to see such intersectionality come together. It is here, for instance, where one can find transgender women of Dominican and Puerto Rican origin lead “houses” of young, many formerly homeless, LGBTQ performers down a runway every weekend to escape a world which is all too often filled with judgment and hate.

Traditionally, many ballroom performers lived on the streets, often pushed into drugs and prostitution to make a living, or that is, just enough to eat and survive. Ballroom “mothers” find these young, vulnerable, outcast youth and give them not only a home but also open the door to a world where they find family and acceptance. In the ballroom scene, it’s more than just dance battles for trophies. Categories like “executive realness” give Black and brown LGBTQ youth the chance to dress up like TV weathermen, women CEOs, and even famous politicians and celebrities in an effort to best imitate or even mock the traditional successful white stereotypes in society. Sadly, Black and brown people of color are not given the same opportunities as their white counterparts, especially when we compare Black and brown workers to heterosexual white workers.

This Pride Month, after four years of setbacks imposed by the Trump administration and over a year of the devastating pandemic, it is important for us to not only celebrate diversity but also reflect on the origins of such diversity. Why does mainstream (mostly white) LGBTQ culture and even pop culture use lingo developed in the 1970s and 80s in the ballroom scene? Why did it take white-dominated drag shows (eventually evolving into the mainstream television competition show RuPaul’s Drag Race) to bring attention to documentaries like Paris is Burning from nearly three decades ago? Would we even know about voguing had it not been for Madonna’s song?

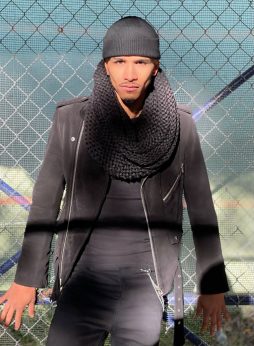

People’s World sat down with a prominent ballroom figure from Season 2 of the television series Legendary who explains his story and views on the authenticity of ballroom culture.

Jamil Branch, the Philadelphia-based “father” of the ballroom House of Icon, was born in 1986 to a working-class African-American mother (who raised him) and an Italian-American father (whom he did not grow up with). His mother and grandmother struggled to put food on the table for four children, two of whom were put up for adoption.

Walking home from school one day, Jamil encountered a group of LGBTQ youth who identified him as one of them. They invited him to attend a dance workshop with them at a local gay dance club called The Attic. This was Jamil’s first time seeing vogue. He continued going to the after school youth program but was soon scared away when transgender folks living with HIV began to show up to give their testimonies as a form of activism.

“I was so young, I didn’t understand these things at the time, and I knew my mother would have a problem with it, so I stopped going,” Jamil told the World. However, his love for dance and his longing to be a part of a community, and his desire to have an LGBTQ family persisted.

A few years later, Jamil encountered Amina and Kevin from the House of Prodigy, who taught him how to vogue and took him to his first ball on a Friday night. It was there, he says, that he felt himself “in that freedom for the first time.” From there, he began attending balls at the Clubhouse in New York City on Thursday nights. There he met Ashley, the mother of the House of Icon, in 2005.

“I saw her dance, I saw her presence and confidence, and I wanted to be just like her,” Jamil says. “I asked to be a part of her house, and she said, ‘We can make this happen.’ Then she put me out there to walk a Butch Queen Vogue Femme category (masculine figure dancing like a female) to represent.” From then on, Jamil has been a proud member of the House of Icon, which he became father of in 2015.

The House of Icon was founded in New York City in 1999. A relatively new house compared to the more established ballroom houses of the 1980s, the House of Icon is small, having about 50 members between NYC and Philadelphia.

“We were seen as underdogs going into Season 2 of Legendary,” says Jamil. “A lot of people didn’t expect us to be there.” Jamil helped build up the House of Icon in Philadelphia, where he recruited Mike, Champagne, and Ziggy. “We recruit based on building a family. We want to see you represent, not necessarily win,” stated Jamil.

“I remember we dressed up like clowns and jesters way back during the 2008 Awards Ball, and I won the grand prize for walking in the Butch Queen Vogue Femme category. It was one of the proudest moments of my life because my house family already loved and accepted me, but now I had proven myself to the entire ballroom community.”

Jamil, a gay Black man from West Philadelphia, commented on how his family, particularly his religious mother and grandmother, did not even truly know who he was as a performer until they watched Season 2 of Legendary when it aired earlier this spring.

“I have no regrets except I wish we had more time to make our outfits for the first week of competition. Some saw us as the ‘weakest house’ due to us being pressed for time, but we turned out and lasted five weeks into the competition,” commented Jamil. Leiomy Maldonado, a Legendary judge and a ballroom icon in her own right, told Jamil when his house was eliminated, “You are one of my favorite voguers from our generation.”

Megan The Stallion, a rapper and Legendary judge, commented on Jamil’s house leadership being that of a “true family full of love,” whereas other houses came across as cold and trying to be too professional.

When asked about advice he might have for younger generations of Black and brown LGBTQ people who watch him on Legendary in secret under the covers at night, Jamil responds: “Be yourself and have fun. Know that there is family for you out there and that people are going to talk about you anyway, so be confident.”

Of course, there is a lot more still unseen and unknown about ballroom culture by society at large. Mainstream TV shows about the ballroom scene are choreographed, unlike the sporadic and often improvised vogue battles which take place in the underground scene. But thanks to the passion and dedication of Jamil Icon and other members of the ballroom community, the world is finally getting to know the working-class Black and brown roots of a big part of contemporary LGBTQ culture. In a country where minorities continue to struggle to be seen, the ballroom scene continues to build its houses by saving homeless and outcast LGBTQ youth.